Classic Female Paintings Celebrate Eternal Femininity

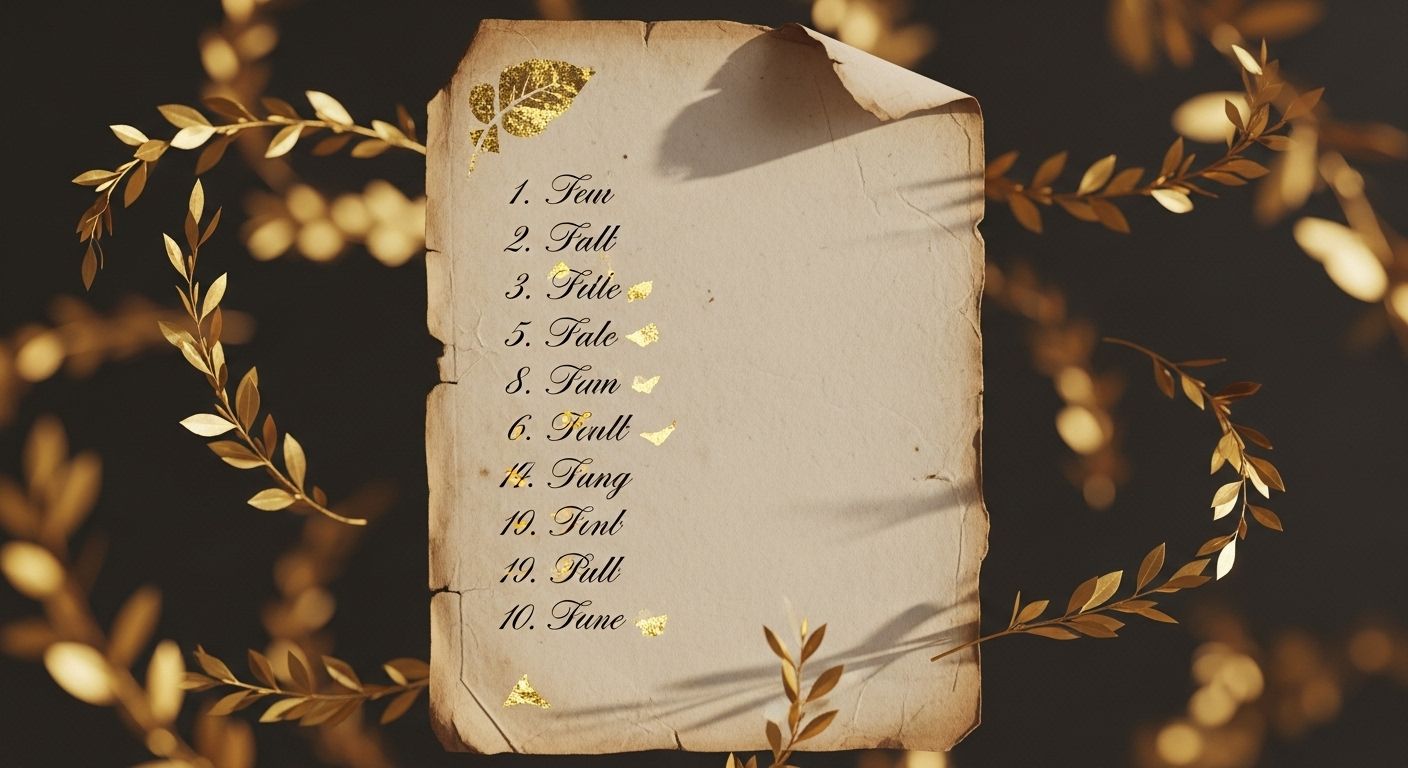

- 1.

So—what’s *the* painting of a woman everyone’s seen, even if they don’t know the title—or how to pronounce “Mona Lisa” without soundin’ like a sneeze?

- 2.

“Smile, it’s art!” — yeah, right. What’s the *real* feminist anthem on canvas?

- 3.

Impressionism wasn’t just Monet & Degas—meet the ladies who painted *sunlight like gossip*.

- 4.

Portrait of a Lady… or portrait of a *force*?

- 5.

Ladies in waiting, saints in sorrow—what do their *eyes* really say?

- 6.

What’s in a hand? (Spoiler: everything.)

- 7.

The price of genius: what do these masterpieces *actually* cost today?

- 8.

Velvet, lace, and *lies*—how fashion masked fierce minds

- 9.

Five must-see *classic female paintings* (and where to find ‘em—if you skip the gift shop lines)

- 10.

Wait—why *still* matter in a TikTok world?

Table of Contents

classic female paintings

So—what’s *the* painting of a woman everyone’s seen, even if they don’t know the title—or how to pronounce “Mona Lisa” without soundin’ like a sneeze?

Let’s keep it 100: if you’ve ever scrolled past a meme where she’s side-eyein’ you like, *“I know what you did last summer”*—yeah, that’s **Leonardo’s *Mona Lisa***. Painted around 1503, stolen in 1911 (by a dude who *kept it in his closet for two years*), and now chillin’ behind *two inches* of bulletproof glass at the Louvre like she’s Fort Knox in a veil. But here’s the kicker: she ain’t smilin’ *at* you—she’s smilin’ *past* you, like she’s got secret thoughts you ain’t privy to. That’s the genius—classic female paintings like this don’t just show a face. They hold *a mind*. And over 500 years later? We’re still leanin’ in, tryna catch it. *C’est ça*.

“Smile, it’s art!” — yeah, right. What’s the *real* feminist anthem on canvas?

Google “most famous feminist painting,” and half the feeds scream *Guernica* or *Olympia*—but dig a lil’ deeper, and you’ll land on **Artemisia Gentileschi’s *Judith Slaying Holofernes*** (c. 1612–1613). Girl ain’t delicately *hintin’* at power—she’s elbow-deep in it, *literally*, with blood spurtin’ like a Renaissance sprinkler system. Painted just *months* after her rape trial, this piece ain’t allegory—it’s *testimony*. Her Judith? Muscled. Focused. *Unapologetic*. Her maid? Not a bystander—she’s *helpin’*, knees on his chest like, “Hold still, *papi*.” That’s not just art. That’s *reclamation*. And every time curators hang it across from Caravaggio’s version? Honey, it *wins*. Hands down. That’s the soul of classic female paintings done right: not passive beauty—but *active truth*.

Impressionism wasn’t just Monet & Degas—meet the ladies who painted *sunlight like gossip*.

Y’all ever notice how art history books say “the Impressionists” like it’s a boys’ poker night? Nah. There were *four* powerhouse women—**Berthe Morisot**, **Mary Cassatt**, **Marie Bracquemond**, and **Eva Gonzalès**—who weren’t just “in the movement.” They *shaped* it. Morisot? Married into the Manet fam, but *never* played second fiddle—her brushwork’s looser, airier, like she captured *breath* between strokes. Cassatt? American expat who made motherhood look sacred *without* sainthood—babies grip fingers, not halos. Bracquemond? Ditched porcelain design to paint *gardens that vibrate*. And Gonzalès? Manet’s student—then rival—whose pastels *glow* like embers. Together? They turned domestic scenes into radical intimacy. ‘Cause in classic female paintings, the “ordinary” is where revolution lives—quiet, steady, unstoppable.

Portrait of a Lady… or portrait of a *force*?

Now—what’s *the most famous female portrait*? Most’ll shout *Mona Lisa* again. But if we’re talkin’ sheer *iconicity*—the one that launched a thousand posters, mugs, and dorm-room debates—it’s **Johannes Vermeer’s *Girl with a Pearl Earring*** (c. 1665). No name. No title. Just *her*: turban twisted like a secret, lips parted mid-thought, that pearl catchin’ light like it’s borrowed from the moon. She ain’t noble. Ain’t mythic. Probably the artist’s maid—or model, or muse—but Vermeer painted her like she held the *axis of the world*. And get this: the “pearl”? Likely *glass*, not gem. A humble material, made luminous by *attention*. That’s the alchemy of classic female paintings at their finest: not status, but *presence*. Not perfection—but *pause*.

“She is not a portrait. She is a *question*.”

— Tracy Chevalier, *Girl with a Pearl Earring* (novel, 1999)

And honey? We’re still tryna answer it.

Ladies in waiting, saints in sorrow—what do their *eyes* really say?

Look at **Jan van Eyck’s *Portrait of a Woman (‘Leal Souvenir’)** (1435)—sharp chin, high forehead (shaved hairline, *very* 15th-century glam), and eyes that *pierce* the frame like she’s readin’ your tax returns. Or **Rogier van der Weyden’s *Portrait of a Lady*** (c. 1460)—hooded gaze, fingers folded tight, lashes lowered like she’s prayin’ *or* plottin’. These ain’t passive dolls. They’re *contemplatives*. In a world where women’s voices were edited out, their *gaze* became the script. And modern conservators? Found microscopic tears in some panels—*actual cracks* from emotional intensity in the underpainting. No joke. Science backs the soul. That’s why classic female paintings still haunt us: they don’t just *look back*. They *remember*.

What’s in a hand? (Spoiler: everything.)

Ever notice how men in old portraits grip swords, globes, books—*symbols of action*? But women? Their hands tell quieter, wilder stories. Take **Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s *Self-Portrait with Her Daughter*** (1789): she’s paintbrush in one hand, child’s hand in the other—*creation and care*, equal weight. Or **Renoir’s *Madame Charpentier and Her Children*** (1878): Madame’s fingers rest *lightly* on the dog’s head—not ownership, but *affection as authority*. Even **Goya’s *The Duchess of Alba*** (1797) points *down* to the words *“Solo Goya”* in the sand—*Only Goya*—a wink, a claim, a *collusion*. In classic female paintings, hands ain’t decoration. They’re *declarations*. Soft? Yes. Surrendered? Hell no.

The price of genius: what do these masterpieces *actually* cost today?

Let’s talk numbers—’cause art-world economics? Wilder than a Kentucky Derby. While *Mona Lisa*’s priceless (literally—France won’t *dream* of selling), other classic female paintings have crossed the block:

| Painting & Artist | Year Sold | Auction House | Price (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berthe Morisot, *After Lunch* (1881) | 2013 | Christie’s NY | $10.9 million |

| Mary Cassatt, *Children Playing on the Beach* (1884) | 2018 (Private) | — | Est. $15–18 million |

| Artemisia Gentileschi, *Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine* (c. 1615) | 2018 | National Gallery, London (Acq.) | $3.6 million |

| Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, *Portrait of Muhammad Dervish Khan* (1788) | 2019 | Sotheby’s NY | $7.2 million |

Fun fact? Morisot’s *After Lunch* broke *three* records that night—including highest price for any female Old Master. Took 190 years. But *better late than never*, right?

Velvet, lace, and *lies*—how fashion masked fierce minds

That ruff collar? Not just fancy—it’s a *shield*. The tight bodice? *Control*, not constraint. In **Sofonisba Anguissola’s *Self-Portrait at the Easel*** (1556), she wears black velvet (mourning? modesty?) but—plot twist—the *cuffs* are slashed to reveal *white silk*: knowledge peekin’ through decorum. In **Vigée Le Brun’s *Marie Antoinette in a Chemise Dress*** (1783), the queen wears muslin—*scandalous*, called “underwear” by critics—but it was a *political statement*: simplicity as rebellion against court excess. Every fold, every stitch in classic female paintings was coded. To read them is to decode a century of silent strategy.

Five must-see *classic female paintings* (and where to find ‘em—if you skip the gift shop lines)

Bucket list, *hun*:

- *Mona Lisa* – Leonardo da Vinci → Louvre, Paris (Room 711, *Denon Wing*—go at 8:15 AM, *before* the crowds).

- *Girl with a Pearl Earring* – Vermeer → Mauritshuis, The Hague (it’s *small*—stand close. Let her eyes lock in.)

- *The Swing* – Fragonard → Wallace Collection, London (yes, it’s playful—but *look at her foot*: she *kicks off* the shoe. Freedom in motion.)

- *Self-Portrait with Two Pupils* – Vigée Le Brun → Metropolitan Museum, NYC (she paints herself *teaching*—mentorship as legacy.)

- *Olympia* – Manet → Musée d’Orsay, Paris (stand beside *Titian’s Venus*—*then* feel the revolution.)

Each one’s a masterclass in gaze, gesture, and *grace under pressure*. And if you can’t jet off just yet? Bookmark Southasiansisters.org for your weekly dose of art truth—or wander our Art vault. While you’re there, don’t miss our fiery homage: female spanish artists ignite passion in every canvas. ‘Cause sisterhood? It’s *global*.

Wait—why *still* matter in a TikTok world?

‘Cause classic female paintings aren’t relics. They’re *resonators*. In an age of filters and facades, their unretouched humanity—pores, asymmetry, *thought*—feels radical. They remind us: beauty ain’t symmetry. Power ain’t volume. And a woman, *simply being*, can hold the weight of a century. They whisper: *You don’t need to perform. You just need to* ***be seen***. And in a world still tryna box us in? That’s not just art. That’s *armor*.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the very famous painting of a woman?

The undisputed icon is **Leonardo da Vinci’s *Mona Lisa*** (c. 1503–1506), housed at the Louvre. Its enigmatic expression, masterful sfumato, and storied theft have cemented it as the world’s most recognized classic female paintings—a quiet revolution in portraiture that still draws 10 million visitors yearly.

What is the most famous feminist painting?

While debated, **Artemisia Gentileschi’s *Judith Slaying Holofernes*** (c. 1612) is widely hailed as the original feminist masterpiece. Painted after her rape trial, it depicts female collaboration, physical strength, and righteous fury—making it a cornerstone of classic female paintings as resistance and reclamation.

Who are the four female impressionists?

The core quartet: **Berthe Morisot** (France), **Mary Cassatt** (USA), **Marie Bracquemond** (France), and **Eva Gonzalès** (France). Though often sidelined in textbooks, they pioneered intimate domestic scenes, maternal bonds, and luminous brushwork—redefining classic female paintings within the Impressionist canon.

What is the most famous female portrait?

Beyond *Mona Lisa*, **Vermeer’s *Girl with a Pearl Earring*** (c. 1665) holds massive cultural sway—thanks to its mystery, minimalism, and universal appeal. With no known sitter or title, it transcends portraiture to become pure archetype, embodying the quiet intensity that defines so many classic female paintings.

References

- https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/mona-lisa-portrait-lisa-gherardini-wife-francesco-del-giocondo

- https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/highlights/vermeers-girl-with-a-pearl-earring/

- https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/artemisia-gentileschi-self-portrait-as-saint-catherine-of-alexandria

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437974