Greek Paintings of Women Revive Ancient Graceful Myths

- 1.

Y’all ever wonder why every time we think “ancient beauty,” some marble-lipped lady in a draped chiton pops into our heads?

- 2.

Were Greek ladies just background fluff—or did they get the spotlight?

- 3.

Wait—pitchfork? Woman? Man? Hold my ouzo…

- 4.

What’s the *very* famous painting of a woman? (Spoiler: she’s not Greek—but let’s talk influence.)

- 5.

Who *was* the Greek goddess of women—and how’d she show up in paint?

- 6.

How’d they even *paint* back then? Egg yolk, marble dust, and pure nerve?

- 7.

What about *real* women—not just goddesses? Did they get painted too?

- 8.

How did Roman copies keep the greek paintings of women alive?

- 9.

Why do these images *still* move us—2,500 years later?

- 10.

Where can you dive deeper into the world of greek paintings of women without needin’ a time machine?

Table of Contents

greek paintings of women

Y’all ever wonder why every time we think “ancient beauty,” some marble-lipped lady in a draped chiton pops into our heads?

Like—seriously—how’d a buncha folks who didn’t even have Instagram *or* contour kits leave behind images that still slap harder than a summer thunderstorm? It’s the greek paintings of women, darlin’—not just stone statues (though bless ‘em), but *paintings*—on vases, walls, wood panels—that whispered elegance, power, and divine drama long before oil paint was even a twinkle in a Renaissance dude’s eye. Now hold up—yes, most classical Greek panel paintings are gone (thanks, time + humidity + Roman looters). But what survives? Oh honey. Vase fragments, fresco shards, literary clues, and Roman *copies* that cling to the originals like ivy on a temple column. The greek paintings of women weren’t just decoration—they were theology, politics, and gossip, all rolled into one swirling drapery.

Were Greek ladies just background fluff—or did they get the spotlight?

Let’s bust a myth faster than Hermes on Red Bull: women in Greek art weren’t *just* passive ornaments—though yeah, plenty got stiff, idealized treatment. Real talk? Portrayal depended on *who* she was—and *who was lookin’*. Mortal women? Often shown in domestic scenes: spinning wool, prepping libations, sayin’ goodbye to warriors headin’ off to die poetic deaths. But the greek paintings of women shift *dramatically* when goddesses enter the frame—Athena stridin’ in full armor, Artemis with bow drawn, Aphrodite risin’ from foam like she *invented* the slow-mo entrance. Even mortal heroines—Helen, Medea, Penelope—got layered treatment: beauty *and* danger, loyalty *and* rage. A 5th-century BCE kylix in Boston? Shows a woman painting *herself* in a mirror. Meta? Or just ancient self-care? The greek paintings of women whisper: *We were seen. We were complex. And sometimes—we held the brush.*

Wait—pitchfork? Woman? Man? Hold my ouzo…

Oh sweet mercy—no, no, no. That ain’t Greek. That’s *Midwestern*. 😅 The painting with the stern man, the unimpressed woman, and the pitchfork? That’s *American Gothic* (1930) by Grant Wood—*not* some long-lost Delphi fresco. Zero pitchforks in classical Greece (they used *tridents*—Poseidon’s brand, honey). Confusin’ it with Greek art’s like mixin’ baklava with apple pie: both sweet, both layered—but one’s got phyllo, the other’s got crust. The greek paintings of women lean *hard* into flow, grace, and divine symbolism—not farm tools and judgmental side-eye. Though honestly? If Athena *did* pose with a pitchfork? We’d stan. (She’d probably forge it herself, tbh.)

What’s the *very* famous painting of a woman? (Spoiler: she’s not Greek—but let’s talk influence.)

“Very famous” usually means *Mona Lisa*—Leonardo’s smirkin’, enigmatic queen in green and gold. But—plot twist—her *aesthetic DNA*? Deeply Greek. That sfumato haze? Inspired by descriptions of Apelles’ (4th c. BCE) lost masterpieces—paintings the ancients *raved* about like they were TikTok virals. Pliny the Elder gushed about Apelles’ *Aphrodite Anadyomene* (“Aphrodite Rising from the Sea”): so lifelike, birds tried to land on her! Though the original’s dust, Roman copies and coin depictions show the pose—right hand lifting hair, left arm modestly draped—that echoes in Botticelli’s *Birth of Venus*… and yeah, *indirectly* in Lisa’s coy vibe. So while the greek paintings of women didn’t survive intact, their *ghosts* haunt every famous female portrait since. They set the template: beauty as power, mystery as magnetism.

Who *was* the Greek goddess of women—and how’d she show up in paint?

Step aside, pitchforks—enter **Hera**: queen of Olympus, goddess of marriage, women, and *serious* side-eye (see: Zeus’ side-chicks). But Hera wasn’t the only one. Artemis guarded girls’ transitions; Hestia kept the hearth sacred; Demeter embodied motherhood’s fierce love. And—let’s not forget—Athena: goddess of *wisdom*, war, *and* crafts (including weaving—aka ancient influencer content). In the greek paintings of women, these deities weren’t just pretty faces—they were *archetypes*. A red-figure hydria in the British Museum? Shows Hera enthroned, peacock beside her, scepter in hand—*authority* made visual. Another fragment from Pompeii (yes, Roman, but copying Greek style) depicts Athena weaving the *peplos* for her own statue—divine labor as sacred ritual. The greek paintings of women didn’t just *show* goddesses—they *invoked* them.

How’d they even *paint* back then? Egg yolk, marble dust, and pure nerve?

Let’s geek out on technique—’cause Greek painters were *mad* scientists with brushes. Panel paintings? Done in *encaustic* (hot beeswax + pigment) or *tempera* (egg yolk + powdered minerals). Frescoes? Pigment brushed onto wet lime plaster—*buon fresco* style—so the image *fused* with the wall. Colors? Vivid as a Georgia sunset: Egyptian blue, cinnabar red, malachite green. And gold leaf? Oh yeah—reserved for gods’ halos, Athena’s aegis, Aphrodite’s diadem. A surviving Pitsa panel (6th c. BCE, Greece’s *oldest* painted wood!) shows nymphs in procession—still bright, still sacred, still proof that the greek paintings of women weren’t grayscale morality tales. They *glowed*. Literally.

What about *real* women—not just goddesses? Did they get painted too?

Here’s the tender part: yes—but quietly. Tomb paintings (like those in Macedonia) show mourning women with *actual* tears, arms raised in lament, hair loosened in grief. Not idealized. Not posed. *Human*. A 4th-century BCE grave stele in Athens? Carved (and likely *painted*) to show a young woman handing a bird to her servant—tender, domestic, *loved*. We also know from texts that female painters existed: Iaia of Cyzicus, famed for her ivory miniatures and portraits of women—Pliny said she “worked faster with a brush than with a pencil, and no man could match her skill.” Sadly? Not one work survives. But the *record* does. The greek paintings of women weren’t all divine fantasy—they held space for sorrow, service, and sisterhood too.

How did Roman copies keep the greek paintings of women alive?

Shout-out to the Romans—yes, *them*—for bein’ the world’s first obsessive fan-fic writers. When Greek originals faded or got smashed, Romans commissioned *copies*—in mosaic, fresco, marble—with religious devotion. The *Aldobrandini Wedding* fresco (1st c. BCE, found in Rome)? Likely a copy of a 4th-c. BCE Greek panel: a veiled bride, attendants, gods hovering—all soft folds, emotional nuance, sacred tension. Then there’s the *Herculaneum frescoes*—women reading scrolls, playing lyres, lounging like they run the place. Were they accurate? Maybe 70%. Were they *vital*? Absolutely. Without Rome’s remix culture, the greek paintings of women might’ve vanished like smoke from an altar. Instead? They came back—filtered, but fierce.

Why do these images *still* move us—2,500 years later?

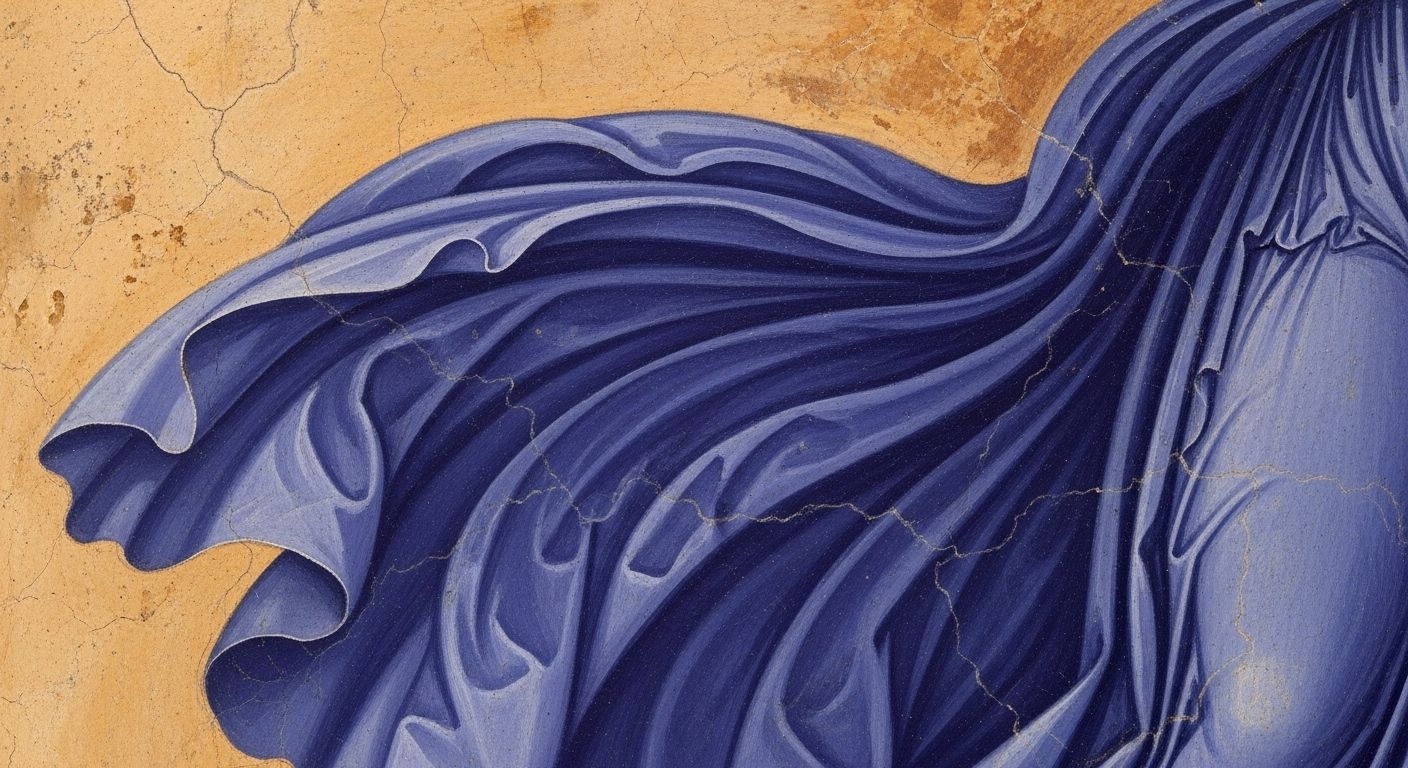

’Cause they nail the *duality*. Greek painters knew: women hold paradox in their palms. Strength *and* softness. Mortality *and* divinity. Submission *and* subversion. A vase in the Louvre shows Pandora lifting the lid—not as villain, but as curious agent: *What if I do?* Another shows Penelope at her loom—unraveling by night, weaving by day—not passive, but *strategic*. The greek paintings of women don’t flatten. They *layer*. Like good baklava. And in a world still arguin’ over who gets to be complex? Yeah—that resonates. We see ourselves in those tilted heads, those knowing glances, those hands that *make*, *mourn*, and *mend*. Also—let’s be real—the drapery physics? *Chef’s kiss.* They made linen look like liquid light. Modern CGI still struggles with that. Respect.

Where can you dive deeper into the world of greek paintings of women without needin’ a time machine?

If your soul’s itchin’ for more goddess energy, mortal grit, and ancient aesthetic genius—we got your back. Start where all journeys begin: at Southasiansisters.org. Then, wander into our curated vault at Art—where every piece tells a story older than your grandma’s sourdough starter. And if you’re feelin’ the Renaissance ripple effect of all this Greek grace? Don’t miss our love letter to a later era: female renaissance paintings showcase timeless beauty. (Spoiler: Botticelli read *all* the Greek fanfic—and took notes.)

Frequently Asked Questions

How were women portrayed in Greek art?

In the greek paintings of women, portrayal varied wildly: mortal women appeared in domestic or ritual roles—spinning, mourning, preparing offerings—while goddesses embodied power archetypes (Athena’s wisdom, Artemis’ independence, Hera’s sovereignty). Though idealized, nuance existed: heroines like Medea or Clytemnestra were shown as intelligent *and* dangerous. Tomb art even captured raw grief, proving the greek paintings of women weren’t just decorative—they were deeply human.

What is the painting with the woman and man with pitchfork?

That’s *American Gothic* (1930) by Grant Wood—not Greek. The greek paintings of women feature flowing drapery, divine symbolism, and naturalistic grace—not pitchforks or Gothic windows. Ancient Greeks used tridents (Poseidon), spears (Athena), or bows (Artemis)—but a three-pronged farming tool? Nah. That’s pure Iowa. Bless its heart, but it’s *not* from the Acropolis.

What is the very famous painting of a woman?

While the *Mona Lisa* tops “famous woman painting” lists, her aesthetic roots trace back to lost greek paintings of women—especially Apelles’ *Aphrodite Anadyomene*, praised for lifelike beauty and soft modeling. Roman copies (like Botticelli’s *Birth of Venus*) kept that legacy alive. So yes, Lisa’s smize is iconic—but the *blueprint*? Ancient Greek. The greek paintings of women invented the language of enigmatic allure.

Who is the Greek goddess of women?

Hera—queen of the gods, protector of marriage and childbirth—is most directly associated with women’s rites of passage. But don’t sleep on Athena (wisdom, crafts, civic duty), Artemis (girls, wilderness, autonomy), or Demeter (motherhood, harvest). The greek paintings of women often blended these roles: a bride might invoke Hera *and* Artemis; a weaver, Athena. Divine portfolios overlapped—just like real life. The greek paintings of women honored that complexity.

References

- https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grpa/hd_grpa.htm

- https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/galleries/ancient-greece

- https://www.theoi.com/Olympios/Hera.html

- https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Plin.+NH+35.90