Medieval Paintings of Women Glow with Sacred Beauty

- 1.

Wait—weren’t all medieval artists dudes in robes named “Brother Something-or-Other”?

- 2.

Saint, scribe, or secret painter? Meet the real medieval “girlbosses”

- 3.

Hildegard, Eleanor, Joan—queen, abbess, or visionary: who *ruled* the era?

- 4.

“Smile, you’re eternal”—what’s *the* painting of a woman everyone knows?

- 5.

The Virgin, the martyr, the mystic—what roles did women *get* to play?

- 6.

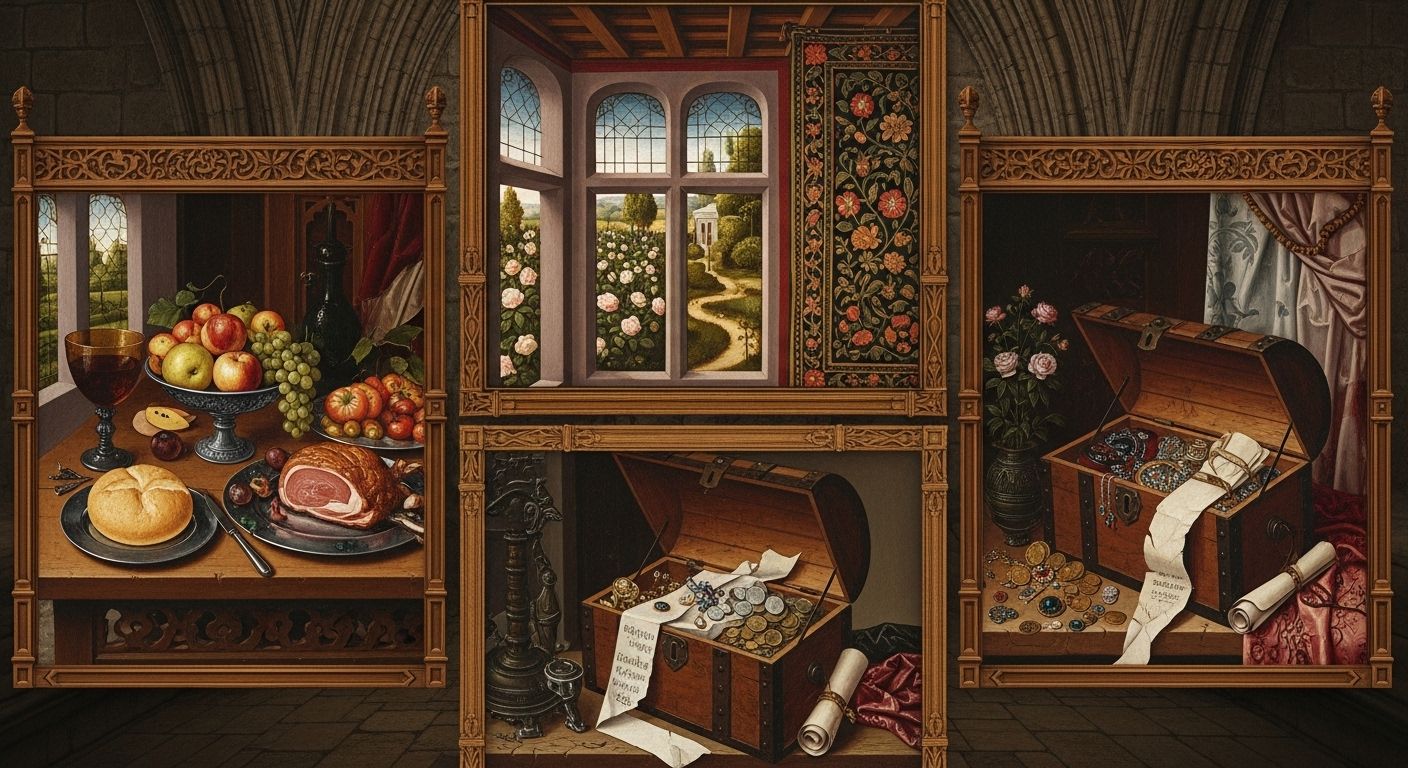

Gold leaf, lapis lazuli, and *sass*—how pigment told power

- 7.

Stats don’t lie: how many *actually* survived—and who’s bringin’ ‘em back?

- 8.

Hands, eyes, feet—why the *details* tell the real story

- 9.

Five must-see medieval gems (and where to *actually* find ‘em—no, not on Etsy)

- 10.

So—why do these centuries-old faces still *stare back*?

Table of Contents

medieval paintings of women

Wait—weren’t all medieval artists dudes in robes named “Brother Something-or-Other”?

Hold up, y’all—before you picture a buncha tonsured monks squintin’ over vellum, let’s spill the *vermillion*-colored tea: yeah, most documented painters *were* men—but the *hands*? Honey, not so fast. Nuns mixed pigments in convent scriptoria. Noblewomen commissioned chapels *and* sketched saints in private diaries. And some—*some*—even signed their work with a flourish. Medieval paintings of women weren’t just *about* women—they were, at times, *by* women. Quiet? Yeah. Erased? Often. Gone? *Nah*. Like gold leaf under grime: still there, waitin’ for light to hit it right.

Saint, scribe, or secret painter? Meet the real medieval “girlbosses”

So—“Who were the women artists in the Middle Ages?” Textbooks stay mum, but manuscripts whisper names: **Ende**, a 10th-century nun in Spain, credited as *“pintrix et dei aiutrix”*—“painter and helper of God”—on the *Gerona Beatus*. *First signed female artist in Western Europe.* Mic drop. Then there’s **Claricia**, a 12th-century Bavarian nun, who doodled *herself*—tiny, swinging from a capital *Q*—in a Psalter like, *“Yep, I’m here. And I’m havin’ fun.”* And don’t sleep on **Guda**, another German nun, who labeled her self-portrait in a homiliary: *“Guda, a sinful woman, wrote and painted this book.”* Humble? Sure. Historic? Absolutely. These weren’t “hobbyists.” They were *theologians with brushes*—and their medieval paintings of women pulsed with devotion, wit, and *dignity*.

Hildegard, Eleanor, Joan—queen, abbess, or visionary: who *ruled* the era?

Ask Google *“Who was the most famous woman in medieval times?”* and three names rise like incense smoke: **Hildegard of Bingen** (1098–1179)—abbess, composer, mystic, *and* naturalist who wrote treatises on medicine while *seeing visions of cosmic eggs*; **Eleanor of Aquitaine** (1122–1204)—queen of France *then* England, patron of troubadours, mother of kings, and political force who outmaneuvered *two* husbands; and **Joan of Arc** (1412–1431)—peasant girl turned war leader, guided by saints, burned at 19, canonized 500 years later. None were painters—but their *images* shaped centuries of medieval paintings of women: Hildegard as radiant visionary, Eleanor as regal strategist, Joan as armored martyr. They proved: a woman’s *presence* could bend history—even if men held the brush.

“Smile, you’re eternal”—what’s *the* painting of a woman everyone knows?

Let’s cut through the tapestry: the *very famous painting of a woman* ain’t medieval—it’s Renaissance (*Mona Lisa*, we see you). But if we’re talkin’ *medieval*? The crown goes to **Jan van Eyck’s *Madonna of Chancellor Rolin*** (c. 1435). Wait—*Jan*? Yep, male painter. But *look at her*: the Virgin Mary, seated beside an ornate loggia, holding the Christ Child, gaze steady, robes rich as midnight wine. She ain’t simpering. She ain’t shrinking. She’s *receiving*—a world, a prayer, a legacy. And behind her? A cityscape so precise, scholars still debate if it’s Autun, Avignon, or *heaven itself*. This ain’t just piety. It’s *power in repose*. And in the canon of medieval paintings of women, she’s the quiet queen we all bow to.

“She does not look at the donor. She looks *through* him—toward eternity.”

— Art historian Erwin Panofsky on the Virgin in *Madonna of Chancellor Rolin*

The Virgin, the martyr, the mystic—what roles did women *get* to play?

In medieval paintings of women, the cast list was tight: Virgin Mary (pure, maternal, *queen of heaven*), Mary Magdalene (repentant, passionate, *human*), saints like Catherine (scholar, wheel-defier) or Barbara (imprisoned, lightning-summoner), and—*rarely*—real women: donors, queens, abbesses. But here’s the twist: even within limits, artists smuggled in *personality*. Look at the *Vierge Ouvrante* (“Opening Virgin”)—a wooden Madonna who *opens* at the belly to reveal Trinity scenes *and* everyday women laboring, praying, birthing. Or the *Hours of Jeanne d’Évreux* (1324–28), where the queen kneels not in supplication, but *conversation* with saints. Medieval painters knew: holiness ain’t passive. It’s *participation*. And every glance, every gesture in these medieval paintings of women? A coded act of witness.

Gold leaf, lapis lazuli, and *sass*—how pigment told power

Let’s geek out on *materials*, ‘cause honey—color was *currency*. Ultramarine blue? Ground lapis from Afghanistan—*more expensive than gold*. And who got drenched in it? The Virgin Mary. Not ‘cause she was “nice.” ‘Cause she was *sovereign*. Red? Vermilion or *cochineal*—for martyrs, queens, the Holy Spirit. Green? For hope, but also *earthly life*—used sparingly on Magdalene’s robes post-conversion. And gold leaf? Not just bling—it was *divine light made solid*. When a 13th-century illuminator laid gold on a nun’s halo in a *gradual*, she wasn’t just “blessed.” She was *illuminated*—literally and spiritually. In medieval paintings of women, every hue had heft. Every shimmer? A sermon.

Stats don’t lie: how many *actually* survived—and who’s bringin’ ‘em back?

Conservators estimate: less than 2% of medieval panel paintings with known female donors *show the woman at equal scale to her husband*. And of surviving illuminated manuscripts, only ~15% feature named female patrons (though evidence suggests *far more*). But the tide’s turnin’:

| Project / Discovery | Year | What Changed |

|---|---|---|

| Rediscovery of Ende’s *Gerona Beatus* attribution | 1990s | Confirmed first signed female painter in West |

| “Women in Illumination” Digital Archive (Getty) | 2021 | 300+ manuscripts tagged w/ female scribes/patrons |

| AI pigment analysis of *Hours of Catherine of Cleves* | 2023 | Found 3 distinct female hands in marginalia |

| Met’s 2024 *She Who Sees* exhibit | 2024 | First major show focused *only* on medieval women makers |

Science + scholarship = resurrection. And every recovered “Claricia swingin’ from a Q”? A *rebellion in ink*.

Hands, eyes, feet—why the *details* tell the real story

Forget the face—*look lower*. In the *Wilton Diptych* (c. 1395–99), the Virgin’s hands cradle Christ with *firm tenderness*—no limp wrists, no decorative pose. In the *Stavelot Triptych* (1156), St. Catherine’s hand *rests on a book* while her foot *presses the spiked wheel*—intellect *and* defiance. Even donor portraits: in the *Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg* (c. 1348), the duchess’s hands are folded—but her *eyes* meet the viewer’s, direct, unflinching. In a world that demanded humility, medieval paintings of women used anatomy as agency. A lifted brow. A squared shoulder. A foot planted *just so*. That’s how you speak when your voice’s been edited out.

Five must-see medieval gems (and where to *actually* find ‘em—no, not on Etsy)

Bucket list for the soul:

- *Gerona Beatus* (c. 975) → Museum of the Cathedral of Girona, Spain — hunt for Ende’s colophon. Tiny. *Titanic*.

- *Madonna of Chancellor Rolin* → Louvre, Paris — Room 801. Stand back. Let the cityscape *breathe*.

- *Hours of Jeanne d’Évreux* → The Cloisters, NYC — ask for the Met’s illuminated manuscript vault. She’s *there*, kneeling in silverpoint.

- *Vierge Ouvrante* (c. 1300) → Musée de Cluny, Paris — open her. *Weep*.

- *Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg* → The Met, NYC — folio 319v: her deathbed portrait. Raw. Real. Revolutionary.

Each one’s a portal—not to a “dark age,” but to a world where women *built*, *prayed*, *resisted*, and *left traces*. For more journeys like this, swing by Southasiansisters.org—or lose yourself in our Art archives. And don’t miss our Texan cosmic dreamer: dorothy hood artist paints cosmic texas dreams. ‘Cause sacred + strange? That’s the *real* lineage.

So—why do these centuries-old faces still *stare back*?

‘Cause medieval paintings of women aren’t relics. They’re *mirrors*. In Hildegard’s visions, we see eco-feminism born. In Claricia’s doodle, the spark of play in constraint. In the Virgin’s unwavering gaze—*sovereignty without spectacle*. They remind us: silence ain’t absence. Ornament ain’t emptiness. And a woman, haloed in gold or scribbling in margin? Can still *shake the world*—one stroke at a time.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who were the women artists in the Middle Ages?

Though rarely documented, key figures include **Ende** (10th c., Spain), the first signed female painter in Western art; **Claricia** (12th c., Germany), who drew herself in a Psalter; and **Guda**, a nun who labeled her self-portrait as “a sinful woman” in a homiliary. Their contributions anchor the legacy of medieval paintings of women as acts of faith *and* authorship.

What is the most famous feminist painting?

While often associated with modern art, many scholars now cite medieval works like the *Vierge Ouvrante*—where the Virgin opens to reveal earthly women in labor and prayer—as early feminist icons. These medieval paintings of women subverted passive imagery, showing female bodies as sites of creation, suffering, and sacred knowledge long before the term “feminism” existed.

Who was the most famous woman in medieval times?

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) stands out: abbess, composer, visionary, and polymath whose writings on theology, science, and medicine influenced popes and emperors. Her legacy—immortalized in medieval paintings of women as a radiant prophetess—cements her as the era’s most enduring female intellectual and spiritual force.

What is the very famous painting of a woman?

While *Mona Lisa* dominates pop culture, the most iconic *medieval* female image is the Virgin in **Jan van Eyck’s *Madonna of Chancellor Rolin*** (c. 1435). Her serene authority, rich symbolism, and revolutionary spatial depth make it a pinnacle of medieval paintings of women—where divinity and dignity merge in oil and gold.

References

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/470073

- https://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/women_illumination/

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ende

- https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/madonna-of-chancellor-rolin